Many LMIC economies, including India are getting crippled due to the surge in non communicable diseases (NCDs). A report titled India – Health of Nation’s States (2019) estimated that 61% of mortality and 55% of the disability adjusted life years were caused by NCDs in 2016 in the country. Common NCDs are cancer, diabetes, cardio-vascular diseases (CVDs), stroke, chronic kidney disease and Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

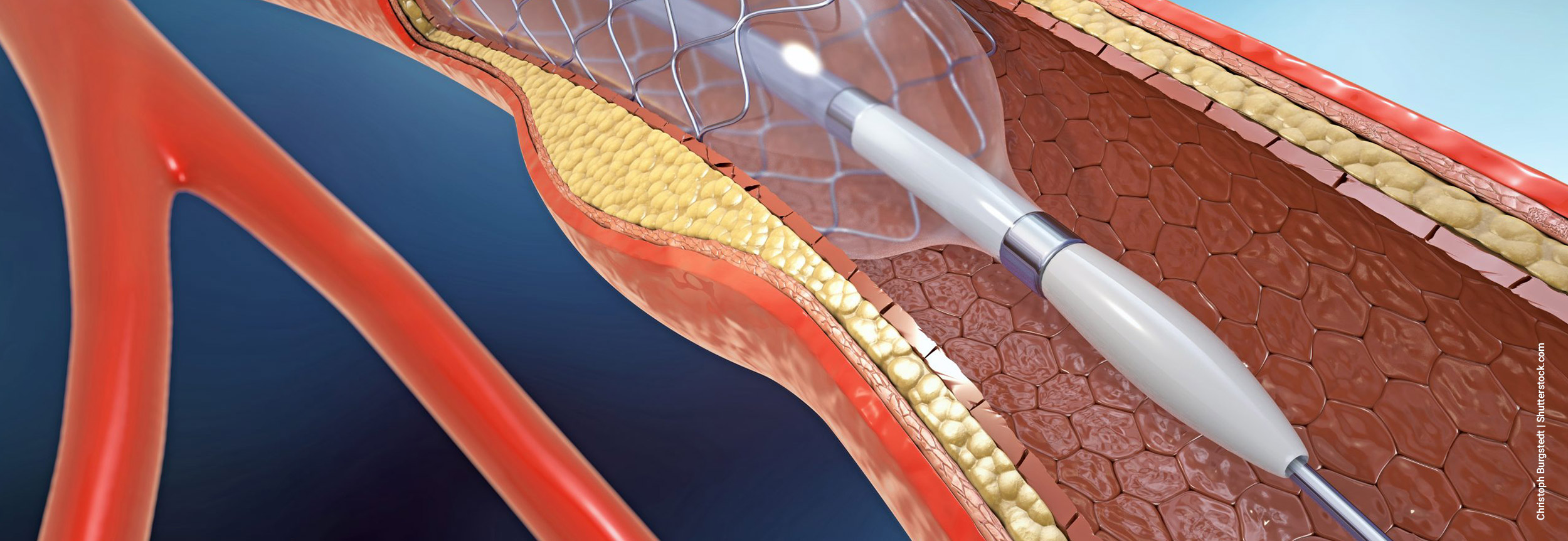

Percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) with stenting and angioplasty is a common treatment in patients with obstructive coronary artery disease (CAD). In a move to bring relief to the pockets of cardiac patients by making stents more affordable, the Central government announced a reduction in the prices of coronary stents by 85% in February 2017. A price ceiling of Rs 7,260 (previously priced at Rs 45,000) for bare metal ones (BMS) and Rs 29,600 (previously priced at Rs 1.21 lakh) for the drug eluting variety (DES), inclusive of all the taxes. Foreign manufacturers complained that the price of production was higher than the new selling price. This demotivated private players, lowering their sales and increasing their keenness on withdrawing premium stents from India.

Coronary stents are used to keep blocked arteries open and to regularize the flow of blood to and from the heart, thus believed to prevent recurrences of heart attacks or death among cardiac patients. Contrary to the above statement, recent research studies found that stents can only offer symptomatic relief and may improve function in the short run but do not offer a permanent solution to reducing the risk of sudden death or future heart attacks in cardiac patients with stable heart disease.

Without a series of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and other health data on the efficacy of invasive procedures (like the stents) over medications and lifestyle modifications in CVD risk reduction, it is unclear why the Central government prioritized one intervention over another. The information constraint or absence of sound data from a reliable data source can hamper a good intentioned policy and can alter outcomes.

With medical research indicating that stents are a short term fix for the chronic, lifestyle illness, it remains unclear why the government is so keen to offer cost relief. The answer lies in India’s higher prevalence (over a crore) and mortality rate due to CVDs and widespread use of stents in healthcare settings.

Price ceiling on stents intended to improve access and affordability. However, it had unintended consequences like most well-intentioned but not well-researched schemes. The price ceiling adversely impacted profit margins of hospitals and led to clinical distortions, forcing hospitals to resort to non-transparent billing on discharge and diverting cardiac patients from coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) procedures to increased emergency usage of percutaneous coronary interventions (PCI). Study also observed pre- and post-price cap policy changes in the type of stent and the number of stents used during the PCI procedure, accounting for up to 60% increased drug eluting stents (DES) and emergency DES procedures while both elective and emergency usage of bare metal stents (BMS) declined sharply by 71% each. The rise in DES procedures could be attributed to the clinical superiority of a DES stent combined with a narrowing of the pricing gap between DES and BMS stents (Deo and group, 2020).

Further, following the price control of cardiac stents, the National Pharmaceutical Pricing Authority (NPPA) revealed that many institutions increased the cost of non-stent components to compensate for their post-price cap losses. These included the prices of balloons and catheters, used during angioplasty.

Individuals and markets have a tendency to analyze policies and schemes to rethink or rework optimizations that work best for them. The price ceiling policy whose intention was to make cardiac invasive devices affordable to all, led to an unintentional distortion in the healthcare system’s choices to compensate for their losses.

In rare cases, misusing stents (in cases of a ≤ 50% blockage with cholesterol plaque), according to a comprehensive report, can result in artery damage, bleeding, stroke, heart attack, or life-threatening blood clots, which can have long-term negative consequences for patients and eventually result in a reduced quality of life for cardiac patients and their families.

As per Bhagwati-Ramaswami theorem, it is always superior to provide interventions to solve the problem at its source rather than providing solutions on consequence. In this scenario, the optimal solution to this lifestyle and public health issue would be for government policies to focus on training primary healthcare staff to play a central role in early screening, spreading awareness and preventing modifiable CVD risk factors.

Government, through the involvement of multiple players, can motivate people of all ages to engage in moderate physical activity (PA) to improve cardiorespiratory fitness including 150-300 minutes per week of any aerobic activity like brisk walking, dancing, sports, jogging, swimming, etc. that raises heart rate and causes it to beat faster than normal. Public health agencies can also consider providing ‘monetary incentives or consumption vouchers’ on the basis of frequency and time spent in a sufficiently intense physical activity. Recent public health research also confirmed that modest financial incentives along with buddies or peers encourage leisure time PA (gymming and walking behavior) and substantially improves the adherence to leisure time PA for longer durations.

Workplace stress reduction strategies also play a key role in reducing mental stress, anxiety attacks, etc. in the working population. Incentives in the form of gym memberships, vouchers for counseling sessions, regular workshops on meditation, yoga, mindfulness training and other stress reduction techniques, flexible timings, etc. can prove effective in controlling modifiable risk factors and preventing CVDs. While these incentives have their merit, in the Indian context, where the majority is employed in the informal sector (81% in 2018), there remain undeniable limitations.

Unhealthy dietary habits are central among the factors that promote blockage of arteries, inflammation and frequent heart attacks. Awareness is the key to curtailing the growing number of cardiac patients. To encourage nutrition-seeking behaviours among consumers, public health messaging can also use celebrities to create awareness. Numerous reforms are already taking place in this direction. This includes enhancing nutrition labels to protect consumers from unhealthy dietary choices.

It is imperative to note that singular motive driven interventions are unlikely to provide the targeted benefit to the public. Therefore, instead of market-distorting policies that tend to have unintended consequences within the healthcare ecosystem, policymakers should focus on strengthening India’s health care in the long term that can be achieved through preventive and sustainable measures.